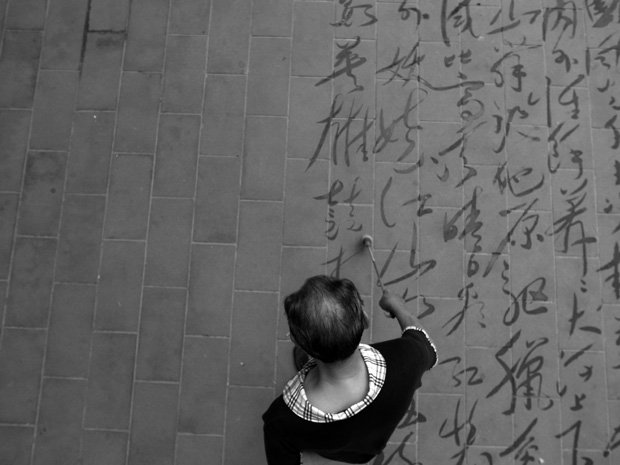

Photos (2)&(3) from francoischastanet.com, (1,4) from dokument.org

A bucket of water, a brush and pavement. These three things make up dishu or “writing calligraphy on the ground”. Art for art’s sake.

Dishu first showed up in the 1990s in Beijing’s Tiantan and Taoranting Park. Elderly over 50 years old would gather and write evaporating proverbs and classic literary lines from poems and prose with selfmade brushes dipped into water on the pavement. Some used sponges, some rolled towels and some used a stick with a tapered sponge on the end and dipped them either in self-made water buckets or in the Taoranting Park’s lake. That was until Bai Yunzhu, the principle of the Taoran branch of the Dishu organization, invented the “baiyun pen” , a brush modeled after Chinese writing brushes. This brush, that is called after him, is now most widely used by practitioners. Similar to some who say that the steel of trains is the best support for sprayed letters, dishu practitioners also distinguish between good and bad surfaces. The best tiles are those that neither allow the water to spread too fast nor absorb the water too fast so that the writing can still be displayed. This is apparently the case with the tiles from the park of Beijing’s Summer Palace (Yiheyuan).

François Chastanet, architect, graphic designer and author of “Pixação” and “Cholo Writing,” documented this practice in 2011 with still and moving images in bigger Chinese cities like Beijing, Xi’an, Shanghai and Shenyang. One result is a book published by Dokument Press in 2013. A quite extensive look into the book is given on Chastanet’s homepage via Issu. Also, more than 40 one-minute long films like the one below can be watched at Chastanet vimeo page.

Leave a Reply